Frei Otto Posthumously Named 2015 Pritzker Laureate #architecture

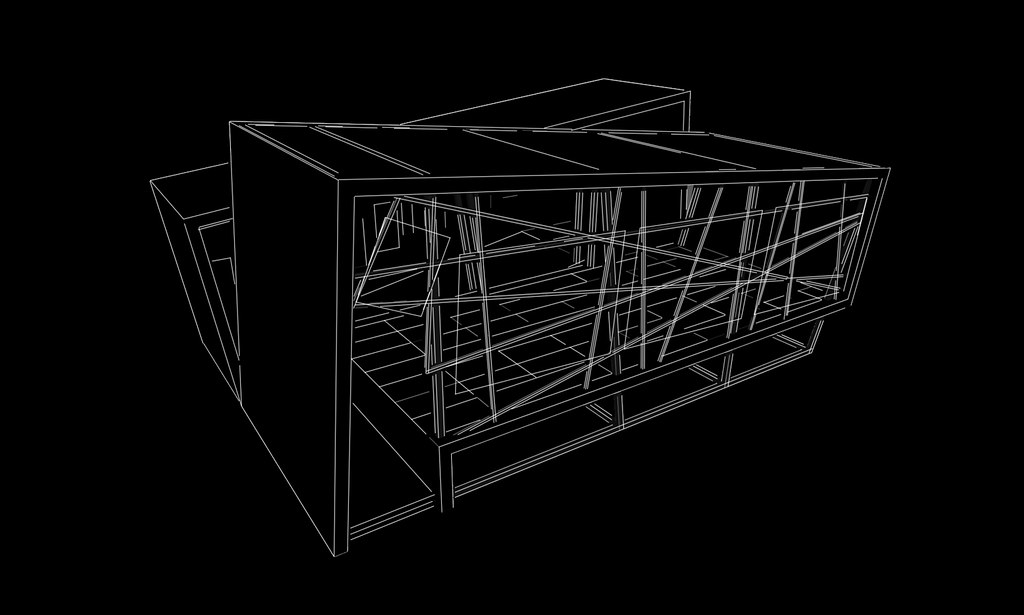

Frei Otto Architect © Ingenhoven und Partner Architekten, Düsseldorf

Frei Otto Architect © Ingenhoven und Partner Architekten, Düsseldorf Roofing for main sports facilities in the Munich Olympic Park for the 1972 Summer Olympics, 1968–1972 Munich, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Roofing for main sports facilities in the Munich Olympic Park for the 1972 Summer Olympics, 1968–1972 Munich, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Roofing for main sports facilities in the Munich Olympic Park for the 1972 Summer Olympics, 1968–1972, Munich, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Roofing for main sports facilities in the Munich Olympic Park for the 1972 Summer Olympics, 1968–1972, Munich, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Hall at the International Garden Exhibition, 1963, Hamburg, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Hall at the International Garden Exhibition, 1963, Hamburg, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn The 1967 International and Universal Exposition or Expo 67, 1967, Montreal, Canada . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

The 1967 International and Universal Exposition or Expo 67, 1967, Montreal, Canada . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn The 1967 International and Universal Exposition or Expo 67, 1967, Montreal, Canada . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

The 1967 International and Universal Exposition or Expo 67, 1967, Montreal, Canada . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Large Umbrellas at the Federal Garden Exhibition, 1971, Cologne, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Large Umbrellas at the Federal Garden Exhibition, 1971, Cologne, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Japan Pavilion, Expo 2000, Hannover 2000, Hannover, Germany . Photos by Hiroyuki Hirai

Japan Pavilion, Expo 2000, Hannover 2000, Hannover, Germany . Photos by Hiroyuki Hirai Japan Pavilion, Expo 2000, Hannover 2000, Hannover, Germany . Photos by Hiroyuki Hirai

Japan Pavilion, Expo 2000, Hannover 2000, Hannover, Germany . Photos by Hiroyuki Hirai Diplomatic Club Heart Tent, 1980, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Diplomatic Club Heart Tent, 1980, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Roof for the Multihalle (multi-purpose hall) in Mannheim, 1970–1975, Mannheim, Germany . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Roof for the Multihalle (multi-purpose hall) in Mannheim, 1970–1975, Mannheim, Germany . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Aviary in the Munich Zoo at Hellabrunn, 1979-1980, Munich (Hellabrunn), Germany . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

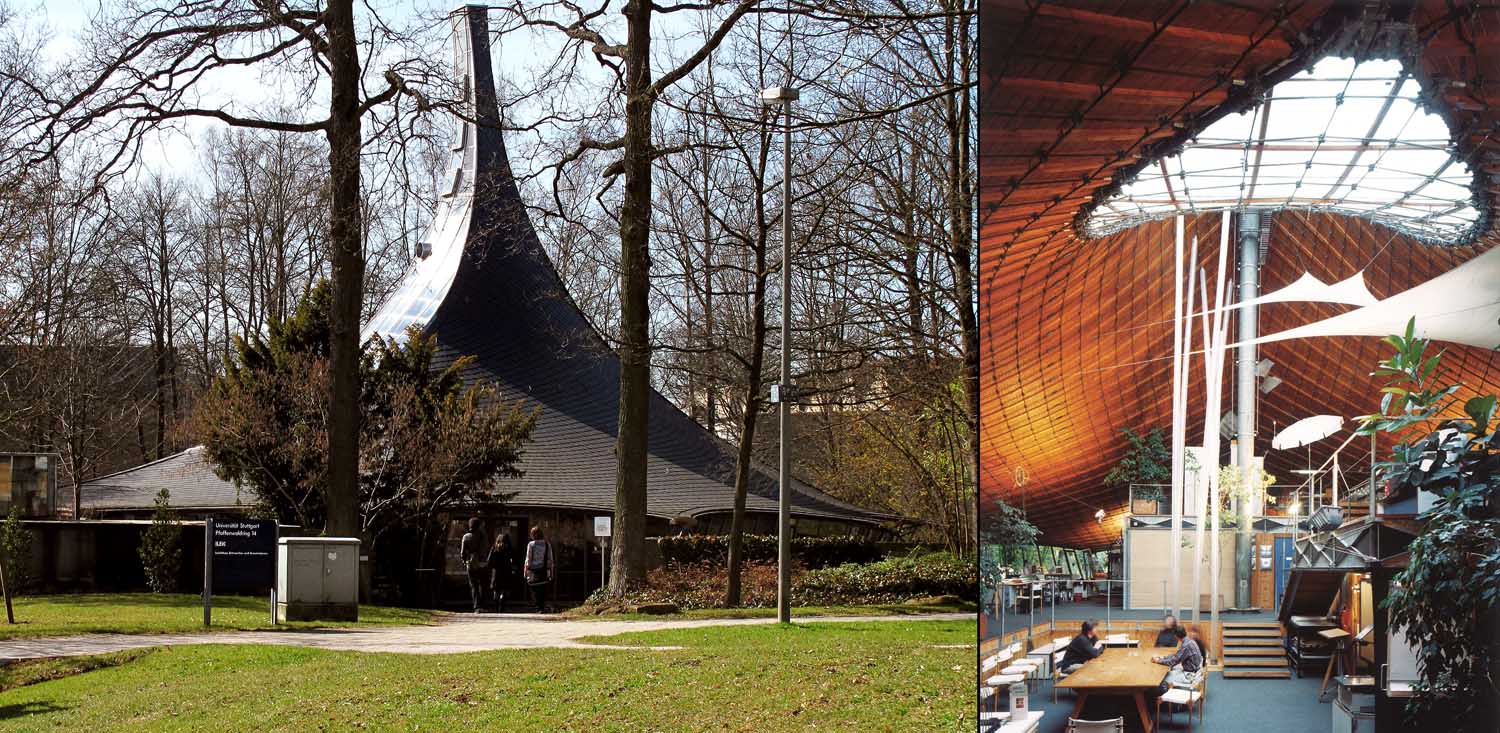

Aviary in the Munich Zoo at Hellabrunn, 1979-1980, Munich (Hellabrunn), Germany . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Institute for Lightweight Structures, interior, 1967, University of Stuttgart in Vaihingen . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Institute for Lightweight Structures, interior, 1967, University of Stuttgart in Vaihingen . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Dance Pavilion at the Federal Garden Exhibition, 1957, Cologne, Germany © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Dance Pavilion at the Federal Garden Exhibition, 1957, Cologne, Germany © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Diplomatic Club, 1980, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Diplomatic Club, 1980, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Bridge in the Mechtenberg Nature Preserve, 2002, The Ruhr region, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

Bridge in the Mechtenberg Nature Preserve, 2002, The Ruhr region, Germany . Image © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Frei Otto © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

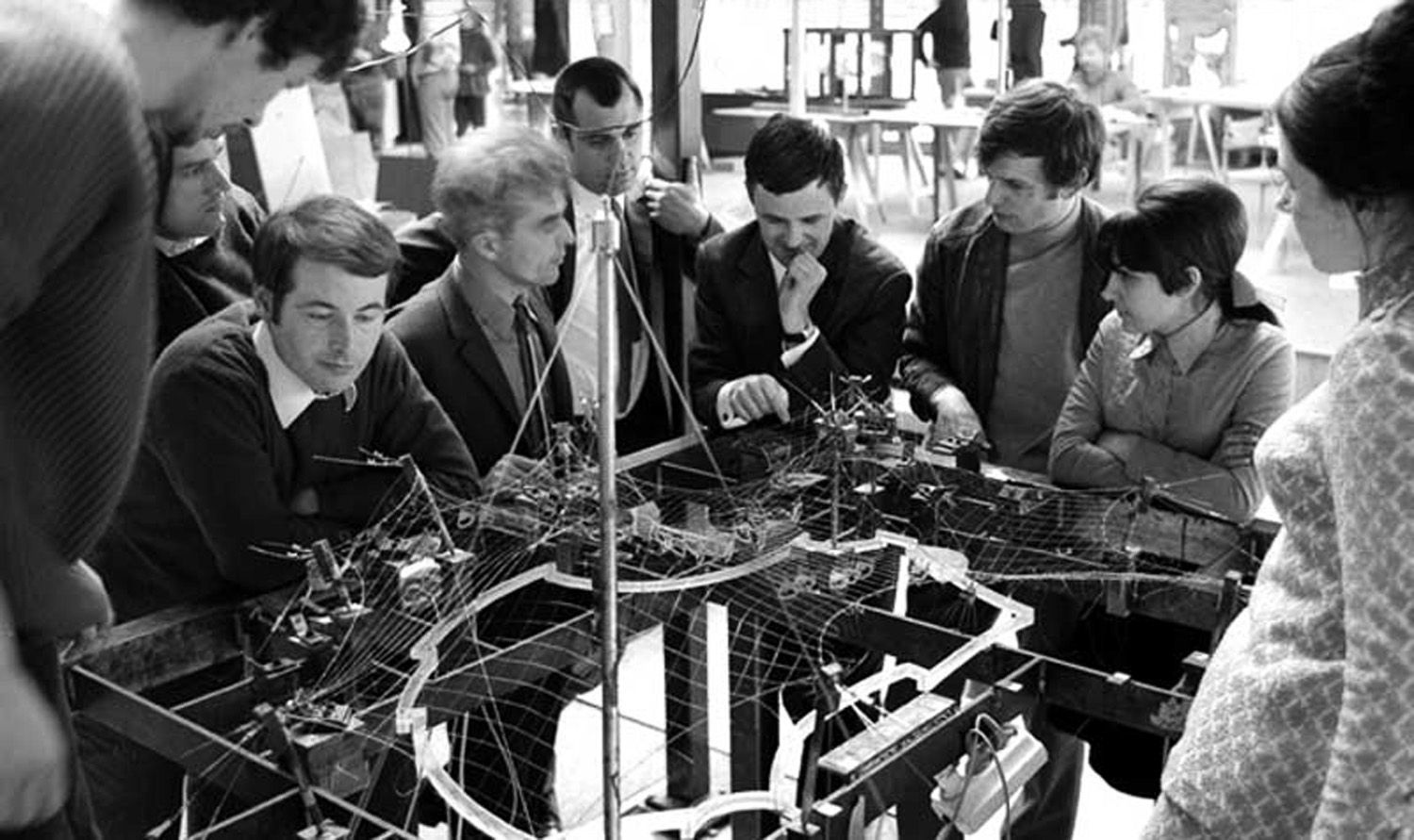

Frei Otto © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn “City in the Arctic” model . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn

“City in the Arctic” model . Photo © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn Frei Otto, Roof for the Multihalle in Manheim – installing the grid

Frei Otto, Roof for the Multihalle in Manheim – installing the grid Jury Citation

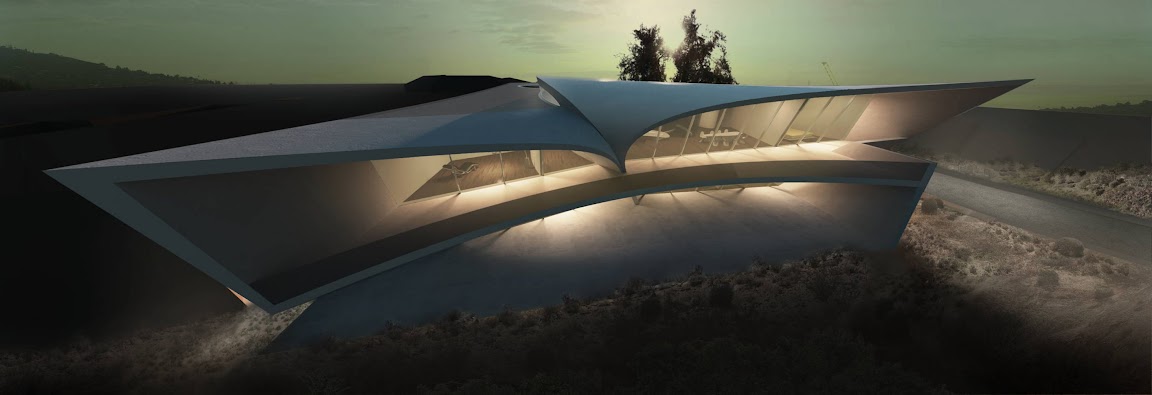

Frei Otto, born almost 90 years ago in Germany, has spent his long career researching, experimenting, and developing a most sensitive architecture that has influenced countless others throughout the world. The lessons of his pioneering work in the field of lightweight structures that are adaptable, changeable and carefully use limited resources are as relevant today as when they were first proposed over 60 years ago. He has embraced a definition of architect to include researcher, inventor, form-finder, engineer, builder, teacher, collaborator, environmentalist, humanist, and creator of memorable buildings and spaces. He first became known for his tent structures used as temporary exhibition pavilions. The constructions at the German Federal Garden exhibitions and other festivals of the 1950s were functional, beautiful, “floating” roofs that seemed to effortlessly provide shelter, and then were easily dissembled after the events. The cable net structure employed for the German Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, prefabricated in Germany and assembled on site in a short period of time, was a highlight of the exhibition for its grace and originality. The impressive large-scale roofs designed for the Munich Olympics of 1972, combining lightness and strength, were a building challenge that many said could not be achieved. The architectural landscape for stadium, pool and public spaces, a result of the efforts of a large team, is still impressive today. Taking inspiration from nature and the processes found there, he sought ways to use the least amount of materials and energy to enclose spaces. He practiced and advanced ideas of sustainability, even before the word was coined. He was inspired by natural phenomena – from birds’ skulls to soap bubbles and spiders’ webs. He spoke of the need to understand the “physical, biological and technical processes which give rise to objects.” Branching concepts from the 1960s optimized structures to support large flat roofs. A grid shell, such as seen in the Mannheim Multihalle of 1974, shows how a simple structural solution, easy to assemble, can create a most striking, flexible space. The Mechtenberg footbridges, with the use of humble slender rods and connecting nodes, but with advanced knowledge, produce an attractive filigree pattern and span distances up to 30 meters. Otto’s constructions are in harmony with nature and always seek to do more with less. Virtually all the works that are associated with Frei Otto have been designed in collaboration with other professionals. He was often approached to form part of a team to tackle complex architectural and structural challenges. The inventive results attest to outstanding collective efforts of multidisciplinary teams. Throughout his life, Frei Otto has produced imaginative, fresh, unprecedented spaces and constructions. He has also created knowledge. Herein resides his deep influence: not in forms to be copied, but through the paths that have been opened by his research and discoveries. His contributions to the field of architecture are not only skilled and talented, but also generous. For his visionary ideas, inquiring mind, belief in freely sharing knowledge and inventions, his collaborative spirit and concern for the careful use of resources, the 2015 Pritzker Architecture Prize is awarded to Frei Otto.

Biography

Frei Otto was born in Siegmar, Germany, on May 31, 1925, and grew up in Berlin. “Frei” in German means “free”; his mother thought of the name after attending a lecture on freedom. Otto’s father and grandfather were both sculptors, and as a young student, he worked as an apprentice in stonemasonry during school holidays. For a hobby he flew and designed glider planes — this activity piqued his interest in how thin membranes stretched over light frames could respond to aerodynamic and structural forces. When he had his university-entrance diploma in 1943, Otto signed up at once to study architecture, but he was not allowed to. Instead, he was drafted into the labor force. In September 1943, Otto was called for military service and he trained as a pilot. The pilot training was stopped at the end of 1944 and Otto became a foot soldier. In April 1945, he was captured near Nürnberg and became a prisoner of war. He stayed for two years in a prisoner of war camp near Chartres in France. There he worked as a camp architect; and he learned to build many types of structures with as little material as possible. After the war, in 1948, Frei Otto returned to study architecture at the Technical University of Berlin. His architecture would always be a reaction to the heavy, columned buildings constructed for a supposed eternity under the Third Reich in Germany. Otto’s work, in contrast, was lightweight, open to nature, democratic, low-cost, and sometimes even temporary. In 1950, with scholarship funds, he embarked on a study trip through the United States, where he visited the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Erich Mendelsohn, Eero Saarinen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, among others. During this time he also studied sociology and urban development at the University of Virginia. In 1952, Frei Otto became a freelance architect and founded his own architectural office in Berlin. He earned a doctorate of civil engineering at the Technical University of Berlin in 1954. His dissertation Das Hangende Dach, Gestalt und Struktur (“The Suspended Roof, Form and Structure”) was published in German, Polish, Spanish and Russian. Also in 1954 he began work with “the tentmaker” Peter Stromeyer at L. Stromeyer & Co. In 1955, he designed and built (with Peter Stromeyer) three lightweight minimal temporary structures made of cotton fabric for the Bundesgartenschau (Federal Garden Exhibition) in Kassel, Germany. These were his first works to gain national recognition, in part for how they harmonized with nature. Frei Otto pioneered the use of modern, lightweight, tent-like structures for many uses. He was attracted to them partly for their economical and ecological values. As early as the 1950s, he built complex models to test and perfect tensile shapes. Throughout his career, Otto always built physical models to determine the optimum shape of a form and to test its behavior. Engineers in his studio were early adopters of computers for structural analysis of Frei Otto’s projects, but the basic input data for these calculations came from the physical form-finding models. In 1958, Otto founded the first of several institutions he would establish that were dedicated to lightweight structures — the Institute for Development of Lightweight Construction, a small private institute — and opened a new studio in the Zehlendorf district of Berlin. Over the next five years he taught periodically in the United States, taking on visiting professorships at Washington University, St. Louis; Yale University; University of California at Berkeley; the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Harvard University. The establishment of the Biology and Building research group at the Technical University of Berlin in 1961 marked the beginning of his cooperative work between architects, engineers, and biologists. They applied their knowledge of tents, grid shells, and other lightweight structures to better understand the designs of biological structures and forms. In 1962, Otto published the first volume of his major opus Tensile Structures: Design, Structure and Calculation of Buildings of Cables, Nets and Membranes (the second volume was published in 1966). In 1964, he became director of the newly founded Institute for Lightweight Structures (Institut für Leichte Flächentragwerke or IL) at the University of Stuttgart. IL was commissioned by the German government to conduct research in connection with the planning of the German pavilion for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal, Canada, better known as Expo 67. The leaders of Germany chose Otto’s architecture to demonstrate the nation’s post-World War II industrial and engineering expertise and innovative technologies. The resulting German pavilion at Expo 67, created in collaboration with Rolf Gutbrod and Fritz Leonhardt, gave Frei Otto his international breakthrough as an architect and a design engineer. It's an early example of a large scale, passive solar building. The following year, in 1968, Otto was named an Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, and IL was commissioned by Olympia Baugesellschaft in Munich to develop construction measurement models for the projected roof of the main sports stadium in the Munich Olympic Park. The project, realized in May 1972, by Günter Behnisch, Frei Otto, and Fritz Leonhardt, for that year’s Olympics, comprised a large membrane to cover the stands of the Olympic stadium, a tensile structure arena, a fabric roof over the Olympic swimming pool, and hyperbolic membrane canopies to connect the buildings and protect visitors from rain and sun. In 1969, Otto established the Atelier (Frei Otto) Warmbronn architectural studio near Stuttgart. There Otto and his teams researched construction methods that could be highly effective with very little material. It happened that the forms of Otto’s buildings often found similar solutions to those in nature and thus resembled natural forms such as bird skulls and spider webs. Otto wrote extensively throughout his career. His book Biology and Buildingwas published in 1972 with a second volume the next year. Later research led Otto to write about the structural and building properties of bamboo, crustaceans, and soap bubbles. In 1994, he published Ancient Architects on structural inventions from the earliest days of building. From 1964 to 1991, Otto was a full professor at the University of Stuttgart, and in 1991, he was named emeritus professor. Over the years, Otto’s research teams would include philosophers, historians, naturalists and environmentalists. He is a world-renowned innovator in architecture and engineering who pioneered modern fabric roofs over tensile structures and also worked with other materials and building systems such as grid shells, bamboo, and wooden lattices. He made important advances in the use of air as a structural material and to pneumatic theory, and the development of convertible roofs. Otto made the results of the research available to other architects. He always favored collaboration in architecture. To cite just two examples: from 1975 to 1980 Otto worked with Rolf Gutbrod and Ted Happold to build a tent-like gymnasium for the King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and Otto co-designed the Japanese pavilion at the 2000 Hannover Expo with architect Shigeru Ban (who received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2014). Frei Otto was recognized with his first major monographic exhibition in 1971 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. (A redesign of the exhibition later traveled in 1975 and 1977 to venues in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia). The exhibition “Natural Constructions,” which featured his work, was organized by the Institute for International Relations in Stuttgart in 1982 and shown in Goethe Institutes in approximately 80 countries. In 1984, he became a founding member of the Special Research Project 230 “Natural constructions — lightweight construction in architecture and nature” of the German Research Foundation, which included the participation of four major universities in Germany. As the largest interdisciplinary German research project, it involved architects, engineers, biologists, behavioral scientists, paleontologists, morphologists, physicists, chaos theorists, physicians, historians, and philosophers. This project was completed in 1995. Among numerous accolades, Frei Otto was awarded the Thomas Jefferson Prize and Medal in Architecture by the University of Virginia in 1974; the Medaille de la recherché et de la technique by the Academie d’Architecture, Paris, in 1982; the Grand Prize and gold medal by the Association of German Architects, also in 1982. He received the 1980 Aga Khan Award for Architecture (together with Rolf Gutbrod) for the conference centre in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and the 1998 Aga Khan Award for Architecture (together with Omrania and Happold) for the Diplomatic Club in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. He was named Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London, in 1982 and Honorary Fellow of the Institution of Structural Engineers, London, in 1986. In 1996, he received the Grand Prize of the German Association of Architects and Engineers, Berlin. In 2005, he was awarded the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). In 2006, the Japan Art Association awarded him the Praemium Imperiale in Architecture.

Tributes to Frei Otto

Lord Peter Palumbo, Chair of the Jury of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Time waits for no man. If anyone doubts this aphorism, the death yesterday of Frei Otto, a titan of modern architecture, a few weeks short of his 90th birthday, and a few short weeks before his receipt of the Pritzker Architecture Prize in Miami in May, represents a sad and striking example of this truism. His loss will be felt wherever the art of architecture is practiced the world over, for he was a universal citizen; whilst his influence will continue to gather momentum by those who are aware of it, and equally, by those who are not. Frei stands for Freedom, as free and as liberating as a bird in flight, swooping and soaring in elegant and joyful arcs, unrestrained by the dogma of the past, and as compelling in its economy of line and in the improbability of its engineering as it is possible to imagine, giving the marriage of form and function the invisibility of the air we breathe, and the beauty we see in Nature.

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureates:

Shigeru Ban, 2014 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Working with Frei Otto was always a lesson in creative thinking. He often used an unexpected approach to find the most appropriate structural solution. I am truly indebted to Frei Otto for sharing his deep understanding and inventions in the field of structures. Norman Foster, 1999 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize I was deeply saddened to hear that Frei Otto had passed away on Monday. On the occasion of his 80th birthday ten years ago I wrote the following tribute: Frei Otto showed us that architecture need not be burdened by the weight of its own traditions, but could instead be free to express itself through simple but innovative sculptural forms — his was an architecture inspired by lightness. This sense of weightlessness, and of an architecture unbound by convention, was carried over into Frei’s working relationships. Rather than working in isolation, he consistently advocated a freer role for the architect — whether this was as an educator, sharing his ideas with generations of students, or in practice, through valued joint projects with, or providing research support for, other architects and engineers. For me, he reinforced the point that architecture is a fundamentally collaborative exercise. His extraordinary structures altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century, and his environmentalism, intelligence and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first. He was an inspiration. Frank Gehry, 1989 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Frei Otto forever changed the way we think about structure and building. Through his experiments in form-finding, Otto simultaneously affirmed and questioned the conventions of engineering as we knew it, and in the process showed us unprecedented solutions to age old problems — where others saw mass as the solution, he offered lightness. Like the ancients and others that came before him, he questioned the origins of our assumptions by going back to nature and figuring it out for himself. There he found systems, networks, and surfaces that exceeded all our imaginations. He found logic in complexity, and proceeded to translate the lessons he learned into efficiently realized constructions. Otto was far ahead of his time in anticipating the issues that would confront the built landscape today: population density, transience, impermanence, energy demands, the growing scale of structures, etc. It is everyone's loss that we will not have his visionary contributions to the conversations of the day. Renzo Piano, 1998 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Frei Otto has been one of the most seminal person on my route to architecture. By the clear determination to work on basic shelters for human communities. And exploring the movement of forces within the structure to make it visible. Celebrating lightness. And fighting against gravity. He succeeded in this and he will always be in my thoughts.

The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2015 Jury:

Alejandro Aravena Throughout his life, Frei Otto has created imaginative, fresh, unprecedented spaces and constructions. He has also created knowledge. Here resides his deep influence: not as forms that were copied but as paths that were opened by his research and discoveries. His contribution to the field of architecture in that sense, has been not only skilled and talented, but also a generous one. Stephen Breyer To speak to architects about Frei Otto is to learn of the great influence that he has had, as a teacher and model, upon modern architecture in Europe and beyond. Kristin Feireiss Frei Otto is considered a genius and one of the most influential architects and visionary spirits of the twentieth century for his pioneering structural inventions, his designs based on deep humanism, his belief in fundamental research and the way he defines architecture as teamwork, — an interplay of collective knowledge of cross-disciplinary experts. Frei Otto has had and has a strong impact on generations of architects from all over the world — and will have it in future. He was always a step ahead his time. Yung Ho Chang Frei Otto is a pioneer for embracing new technologies, from new materials to new structural systems and bringing them into architecture. He has changed our discipline and practice in a revolutionary way. Today's architects are fascinated by the possibility of making lightweight buildings and curvilinear forms. For these interests, Frei Otto can be regarded as a father figure. Glenn Murcutt, 2002 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize In today's media driven culture, too often we are presented with the architecture of novelty and or the spectacular. Architecture is not a short-term proposition; it must remain relevant over time. This year’s recipient has spent his lifetime researching, experimenting, and developing a most beautiful architecture that is timeless. It embodies the purity of lightweight shelter with structures that are economical, simple and are supremely beautiful. The lifelong work of Frei Otto has had and will continue to have a profound international influence on the thinking and work of architects. Richard Rogers, 2007 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize Frei Otto is a revolutionary architect and structural engineer. He is renowned for his development and use of ultra-modern and super-light tent-like structures, and for his innovative use of new materials. He is a great teacher and set up his own Institute for Lightweight Structures at the University of Stuttgart in 1964, making early use of computer modeling to create sensational membrane structures, inspired by natural phenomena — from birds’ skulls to soap bubbles and spiders’ webs. Frei Otto is one of the great architects and engineers of the 20th Century and his work has inspired and influenced modern architecture, as we all learn to do more with less, and to trade monumental structures for economy, light and air. Benedetta Tagliabue When remembering the many projects of Frei Otto or looking at images of them, they bring forth emotions of joy, curiosity, admiration, a wish to imitate and further develop. These strong feelings that the work of 2015 Pritzker winner constantly evokes can be a beacon for us all. more: www.pritzkerprize.com

Source: www.pritzkerprize.com

m i l i m e t d e s i g n – W h e r e t h e c o n v e r g e n c e o f u n i q u e c r e a t i v e s

Since 2009. Copyright © 2023 Milimetdesign. All rights reserved. Contact: milimetdesign@milimet.com